Climb Tafraout Blog

Miscellaneous ramblings, news, views, and anything else we fancied writing about...

MILLENNIUM RIDGE

JANUARY 2018

Lina Arthur on the tremendous 'black wall' (pitch 19) of the 35-pitch millennium ridge at tizgut.

by Steve Broadbent

Tafraout's long ridges have always been alluring routes - from Les Brown's epic explorations of Asgaour's 800m Great Ridge in the mid-nineties, to the race for Aylim's equally long Great Ridge and Labyrinth Ridge in 2007, and the more recent 600m Pinnacle Ridge on Prophet Peak. Efforts on the huge cliffs of Adrar Medni and Jebel Imzi in the Amaghouz Gorge have met with little success, but it's perhaps surprising that Tafraout's longest rock climb should turn up in none other than Tizgut - one of the starting points of Tafraout cragging back in the early nineties.

The south ridge of Upper Prophet Peak is barely visible from any vantage point, lurking as it does behind Tizgut Ridge. Piecing together brief glimpses, photographs, and Google Earth imagery, however, suggested the possibility of a 1000m+ mega-route, which saw its first recce back in November last year.

The ridge starts above the village of Tizgut with 10 pitches of easy climbing to gain an initial tower. From here, a further 3 pitches of steeper ground lead to the Second Tower, beyond which the existence of a continuous ridge was uncertain.

Establishing whether the two ridges were connected was only every going to be possible by getting on the route, so on the 3rd January we left Tafraout at 5am to explore that middle section of ridge.

In the event, perfect climbing conditions made up for the relatively short days, and after starting the route before first light, we had reached the top of pitch 13 by 0920 in the morning, when we gained our first views of the un-photographed middle section. What followed was a real treat - far from fizzling out onto the hillside, the ridge reared up to a fantastic alpine-style ridge-crest, on which we enjoyed pitch after pitch of three-star V.Diff climbing.

Sticking mostly to the very crest of the ridge required two 20m abseils and a tricky downclimb from a prominent gendarme at 1000m, but gave some of the best mountain rock that we'd encountered in the Anti-Atlas.

The whole route featured 1500m of very high-quality, clean rock climbing up to V.Diff standard, completed in 35 pitches to the summit of Upper Prophet Peak.

KSAR ROCK CABLES UPDATE

NOVEMBER 2017

Main rappel anchors on Ksar Rock have now been replaced.

KSAR ROCK CABLE UPDATE

OCTOBER 2017

Unfortunately all cables were removed from Ksar Rock at some point over the summer, and in-situ tat has started to appear at the popular abseil points. Currently the origin or history of this tat is not known, and climbers are advised to carry their own anchors until this situation is resolved.

This affects the following climbs:

- All routes up the Cannon Tower. To descend from the Cannon Tower it is now necessary to leave tat, or climb one of the routes above the Cannon Tower to the summit.

- Routes on the South Face that end on The Catwalk. From the top of these routes it is necessary to scramble up Central Gully to reach the summit.

Ksar Rock Cables

DECEMBER 2015

New abseil cables have been installed on popular descent routes from Ksar Rock following reports of significant corrosion of in-situ anchors.

The anchors affected were the popular Catwalk Rappel Route and the Morocco Coco Rappel, both of which comprised steel cables that had been in-situ for a number of years. Following replacement over the winter, the current cable state is as follows:

The Catwalk Rappel: This anchor has been replaced with a galvanised steel cable. Although it is possible to abseil from here all the way to the base of Paladin with 60m ropes, there is a high chance of getting ropes stuck. Instead, it is recommended to abseil from the Catwalk Rappel anchor diagonally to the top of the Cannon Tower - an abseil of about 26m.

The Palladin Rappel: This anchor comprises in-situ nylon slings around a short spike. Parties should consider taking additional 'tat' to replace the anchor, particularly in the autumn months at the start of the climbing season.

The Cannon Tower Rappel: The original stainless steel chain is in good condition and remains the best descent from the summit of the Cannon Tower, down the line of Lunatic Fringe. This is a 26m abseil.

The Kingping Rappel into Cannon Tower Gully: This anchor now features a new galvanised steel cable.

Morocco Coco Rappel: This anchor was reported as corroded, and has been removed (by an unkown party). Due to the likelihood of stuck ropes, and the availability of the Kingpin and Cannon Tower Rappel routes this anchor has not been replaced.

Adrar Medni - the Mystery Mountain...

OCTOBER 2015

Located to the west of the main climbing areas of the Anti-Atlas, Adrar Medni has remained one of the last great mysteries of Tafraout climbing. Our own adventures with the 'Mystery Mountain', began back in 2008, when we set off to find a way to the base of a mountain that we'd glimpsed from the Dwawj Hairpins the previous year. On that day we actually got fairly close, discovering the outrageous Amaghouz Gorge, and acres of unclimbed rock. We got bogged down in protracted tea drinking, were forced to enjoy tagine in a random village perched high above the gorge, then got hideously lost on the way home, driving along a riverbed to eventually run out of petrol near a town that we'd never heard of. The map that we drew that day posed more questions than it answered; Adrar Medni was going to take some figuring out.

Of course, we were not the first. Claude's team had also spied those towering cliffs during their early explorations of the range, but like us had been unable to figure out any way of attempting a climb. As the years passed, we became aware of more and more teams turning their attentions towards Medni and the Amaghouz Gorge. A few years later, in an attempt to find a way to the summit, we ended up at the foot of the Tighmert Face, disheartened and rather uninspired. In 2013, we tried accessing the gorge from the east: an endeavour that ended in elaborate tagine-eating, near dehydration, and not so much of a whiff of climbing. There was a theme developing...

Rough comparison, showing relative scales of Adrar Medni and the Waterfall Walls / Aylim in Samazar.

From the col, of course, things took a sinister turn. Steep walls of unclimbable, Euphoria-ridden orange quartzite meant we had few options. The ridge crest was not really a ridge crest, and we became unavoidably involved in a tiny, and often rather precarious, shepherd's path. There was no climbing up here! The scale of the Amaghouz Gorge, which now opened up below on our right-hand side was simply staggering. The magnitude of the ridge above us was equally so.

So after about a thousand metres of scrambling, our all-out attempt at Medni's South Ridge stalled. Our advice for future attempts: don't bother - it's not a route, just a collection of scrambles and chossy walls that don't justify the ridiculous logistical challenges! That said, it's an amazing place on a scale unlike anything else in the Anti-Atlas.

And so it was that in October 2015 we arrived at El Jamaa - our chosen starting point for the first 'real' attempt at Medni's now infamous South Ridge. In the intervening years, Neil and Dan had completed a 600m E2 up a 'minor' subsidiary buttress, and Woody's team had 'conquered' the Tighmert Face via their 300m epic E1 "A Hard Day's Night". But it was the South Ridge that stood out from all the others: a massive, endless, ridge of towers and pinnacles that culminated in an attractive-looking 300m final tower.

But it was the impressive stats that were going to be the problem. The Amaghouz Gorge carves through the landscape, blocking any kind of easy access. It's a thousand foot deep, and whilst Berber paths would surely exist, a Berber bridge would be more use. Then there's the route itself: potentially some 12,000ft of climbing with a thousand vertical metres from base to summit. You could stand Aylim's Labyrinth Ridge (the longest route in the Anti-Atlas) on its end four times over...

So here was the first problem: how much water could we carry? Down in the gorge, at 300m above sea level, it was hot and humid. Yesterday it reached 40 celcius in Tafraout, 700m higher. It was obvious that climbing as a pair was impractical due to the weight of rack and ropes, so we set off as a five, heavily laden with big-wall-style supplies of fluids. Woody generously volunteered to look for the descent route and deposit a supply of water on the summit for us.

It turns out that there is indeed a decent path from El Jamaa down into the gorge, and onward to Addar, lying right at the foot of this stunning mountain. We arrived there in the late morning, and to our surprise the climbing began straight away - an awesome little ridge of perfect quartzite that led us up towards the crest of the South Ridge proper. It gave about 500m of excellent easy scrambling... surely this was too good to be true?!

The following day we headed over to Samazar, where everything looked teenie tiny.

Mapping the Anti-Atlas

August 2015

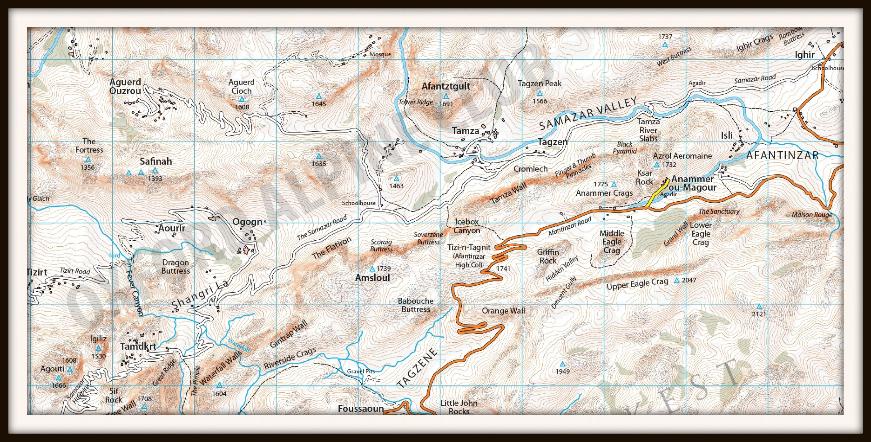

I'll never forget the first time we set foot in the Afantinzar Valley: we'd driven up beyond the Dwawj Slabs, on through Tagzene, and then over a high col without a name. Griffin Rock, Anammer, Ksar Rock, the Eagle Crags... none of them had yet seen the attentions of western climbers, but as we drove down the bumpy dirt road we knew had struck upon a paradise of adventurous trad climbing. Strangely, it was the striking arete of Park End, at Anammer Crags, that was the first route to catch our attention, though its first ascent would wait for another day. Our Ford Fiesta felt a very, very long way from the closest civilisation, and to add to the adventure we didn't even know in which direction that civilisation lay. In my mind, I was already piecing together a map of how we'd got here; and more importantly, how we were going to get out at the end of the day.

In the event, we never did get out of Afantinzar that day, but that's a different story. Over the next few years we pieced together more of the puzzle; new valleys and new crags were opened up each season. Tagzene, Tagmout, Samazar, and the Takoucht Escarpment all became major centres for climbing in the area, and more recently explorations along the Aouguenz Road and into the Amaghouz Gorge have provided dozens of Anti-Atlas climbers with that same, incredible sense of adventure. Along the way, we hunted high and low for decent maps of the area, hoping they would reveal the next 'Afantinzar' without all the effort of mapping it ourselves. But no such luck, and so it was that we started drawing maps...

2007

This was the first map of Afantinzar to appear in the Tafraout Livre d'Escalade in the Amandiers Hotel. Up to this point, the only climbing on the north side had been to Asseldrar (by the original Ameln pioneers, based out of Ait Baha) and the Dwawj Slabs (by Geoff Hornby and team). The name "Afantinzar" (written here with a question mark) was coined from the map in the lobby of the Amandiers hotel, which was the main source of information for accessing the north side in 2007.

2008

Within a year of the first climbs being put up in Afantinzar and Tagzene most of the Afantinzar crags had been climbed and named by western climbers. This updated map in the Livre d'Escalade provided an 'index' for the vast number of new lines now being recorded on these newly named crags. The first forays into Samazar had only just taken place, but the name "Samazar" had already caught on despite being a mis-remembering of "Tamza".

2009

The first work started on a guidebook to the north side of Jebel el Kest, originally in the form of an online web guide. This was the map of Samazar at the time, drawn pretty much from memory and not to scale.

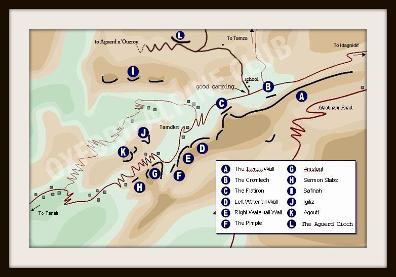

2010

The publication of the "Moroccan Anti-Atlas North" guidebook necessitated better mapping. The main access routes to all the climbing areas were, by now, well understood and drawn accurately to scale. Relief information in this map is still an approximation.

2012

Another new guidebook... and updated mapping. Roads, rivers, and even individual buildings are all correctly illustrated thanks to publicly available data on Google Earth, though terrain data is still a manually drawn approximation. This particular image was a "work-in-progress" for the new guidebook, before the labels were added!

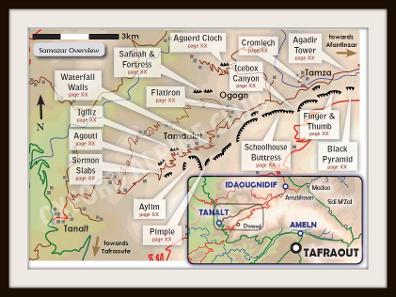

2015

One of the last missions of the Space Shuttle was the "Shuttle Radar Topography Mission" which gathered elevation data for the whole planet. Whilst we were all out in the sunshine, boffins at the Consortium for Spacial Information and USGS were writing some very clever algorithms to analyse a mind-boggling amount of data. Today, it allows us to draw accurate relief maps of the Anti-Atlas, such as this sample from Afantinzar and Samazar.

It may take quite a while for exciting (yes, I am a sad map obsessive) data like this to have an impact on climbing in the Anti-Atlas, but perhaps the days of Tafraout's reputation as being a place where 'you're guaranteed to get lost' are numbered...

You can see some of the production in the video below... including digitizing the roads, rivers, buildings and crags....

Valley Uprising

January 2015

It's tempting to say that every once in a while, something comes along that redefines its genre. In the case of climbing films, it's not even as often as that. It happened once, back in 1998, when Slackjaw Films' legendary grit flick 'Hard Grit' well and truly set the bar for others to follow. Arguably, none have surpassed it: a film that not only inspired a generation, but defined the very sport it described. Now, 16 years down the line, I think it might, finally, have been surpassed.

In fact, let's not beat around the bush. Valley Uprising, by Sender Films, is, actually, the best climbing film that I've ever had the pleasure of watching. I was so gripped for the whole 1hr38m that I couldn't tear myself away, even for a moment. My palms were sweating by the time the opening titles had finished, and they didn't stop doing so until I'd watched right the way through the closing credits, when I was left desperately wanting more. It's a masterpiece, exquisitely produced, controversial, insightful, and for any climber, surely, absolutely fascinating.

Quite how the team at Sender managed to make old black and white photos come alive so vividly I really don't know, but what they've done is as mesmerising as it is impressive. On the face of it, the film tells the story of rock climbing in Yosemite Valley, from the pioneering times of John Salathe to recent big wall solos by Alex Honnold. But unlike almost every other climbing film since Hard Grit, Valley Uprising isn't just about one man, or a clique; people promoting their latest exploits. This film has absolutely, well and truly, hit the nail on the head. It's about climbing, the sport as a whole, and then somehow, so much more... It's got everything a great story needs: from danger and excitement to strong characters, heroes that turn out to be villains, and villains that turn out to be heroes. It's so well made that you don't even think to stop and ask "how on Earth did they film that?" - which you really ought to be asking, given some of the outrageously good footage that is included in this epic production.

Now, I know I'm probably somewhat biased - After all, I'm a devout trad climber, I love Yosemite, have a curious fascination with El Capitan, and am perhaps more interested in the history of climbing than its future... but, do you know what? For once I'm really not sure that matters, for what Valley Uprising has done so well is crystallize the spirit of the sport that unites us, whether we're sport climbers, trad climbers, boulderers, base jumpers... hippies... or perhaps even park rangers. It tells a simple, yet epic story. It tells it beautifully, honestly, and sympathetically. I guess what I'm trying to say is that I simply cannot recommend this film highly enough. Go watch it.